By

Professor Gloria Moss and Niall McCrae

October 19, 2025

October 19, 2025

PUBLICATION of research results, theoretical propositions and scholarly essays is not a free-for-all. As shown by the dogmatism around climate change and covid, sceptics struggle to get papers in print. The gate-keeper is the peer-review system, which most people take for granted as a screening process to ensure rigour in scientific literature.

It is not always been that way. Until at least the 1950s, the decision to publish was made by the editors of academic journals, who were typically eminent professors in their field. Peer review, by contrast, entails the editor sending an anonymised manuscript to independent reviewers, and although the editor makes a final decision, the reviews indicate whether the submission should be accepted, revised or rejected. This may seem fair and objective, but in reality peer review has become a means of knowledge control via groupthink – and as we argue here, perhaps that was always the purpose.

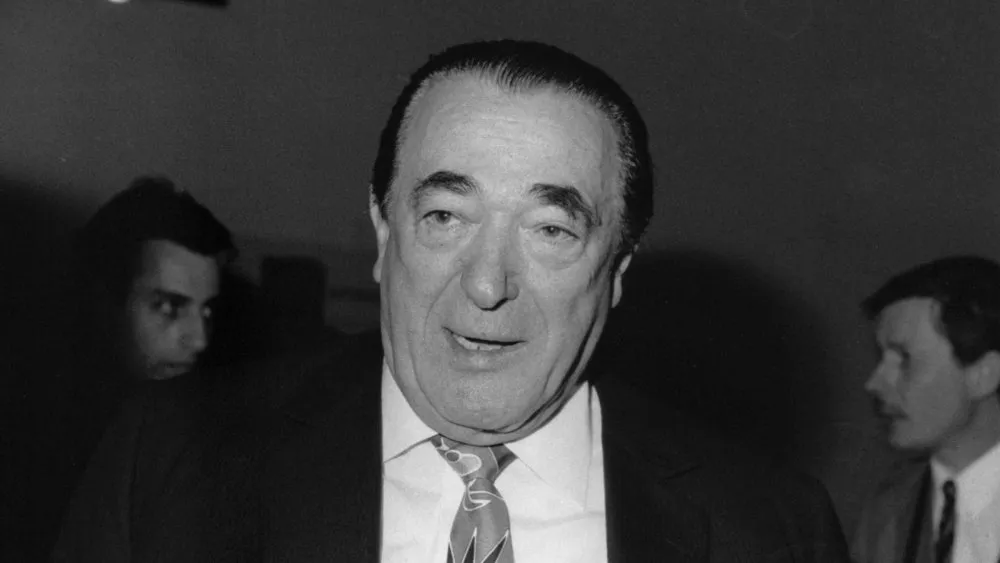

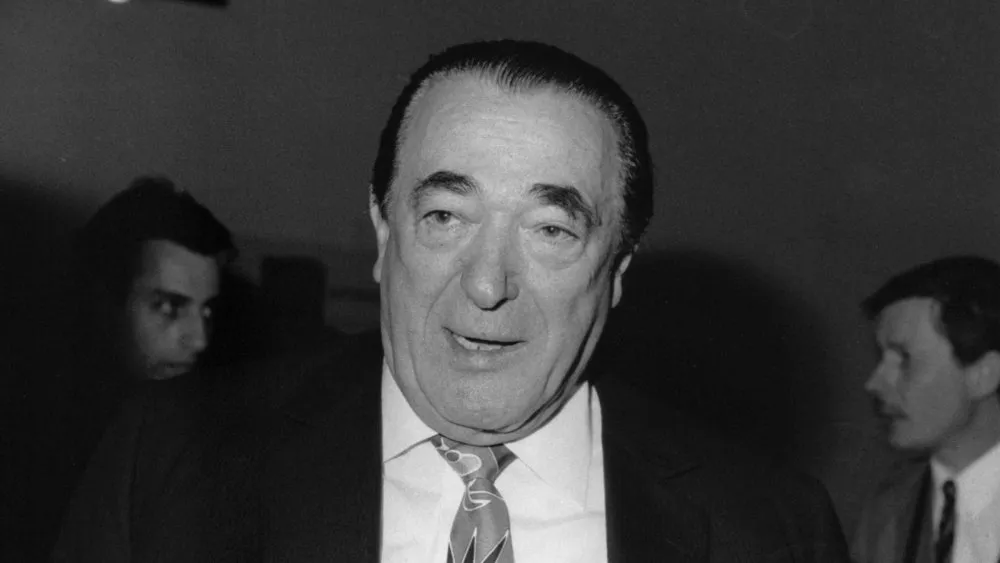

Readers may be surprised to know that the instigator of peer review was the media tycoon Robert Maxwell. In 1951, at the age of 28, the Czech emigré purchased three-quarters of Butterworth Press for about half a million pounds at current value. He renamed it Pergamon Press, with its core business in science, technology and medicine (STM) journals, all of which used peer review. According to Myer Kutz (2019), ‘Maxwell, justifiably, was one of the key figures – if not the key figure – in the rise of the commercial STM journal publishing business in the years after World War II.’

By 1959 Pergamon was publishing 40 journals, surging to 150 by 1965. By 1996, one million peer-reviewed articles had been published. Yet despite the increase in outlets, opportunities for writers with analyses or arguments contrary to the prevailing narrative are limited. Maxwell was instrumental to peer review becoming a regime to reinforce prevailing doctrines and power.

In 1940, Maxwell was a penniless 16-year-old of Jewish background, having left his native land for refuge in Britain. His linguistic talents attracted the attention of the British intelligence services. On an assignment in Paris in 1944 he met his Huguenot wife Elisabeth. After war ended in 1945 he spent two years in occupied Germany with the Foreign Office as head of the press section. Four years later, with no lucrative activity to his name, this young man found the money to buy an established British publishing house. According to Craig Whitney (New York Times, 1991), Maxwell made Pergamon a thriving business with ‘a bank loan and money borrowed from his wife’s family and from relatives in America’.

But how was he able to acquire Butterworth Press initially? A clue is given by a BBC video clip (2022) on Maxwell’s links to intelligence networks. While operating as a KGB agent in Berlin, he presented himself to MI6 as having ‘established connections with leading scientists all over the world’. According to investigative journalist Tom Bower, ‘unbelievably what he really wanted was for MI6 to finance him to start a publishing company’. This point is corroborated by Desmond Bristow, former MI6 officer, who states that Maxwell asked the secret security service to finance his venture. Seven years after launching Pergamon Press, Maxwell moved into Headington Hill Hall, a 53-room mansion in Oxford, which he leased from Oxford city council.

If it was the intelligence services (British and/or Russian) that bankrolled Pergamon Press, their motive could have been to ensure control of knowledge following the tremendous advances of the Second World War (such as nuclear physics and weapons of mass destruction). Maxwell’s choice of name for his venture is interesting. The ancient site of Pergamon was allegedly the locus of Satan’s throne (Revelation, 2:12), and a cynic might suggest that Maxwell’s peer review system would turn science from Enlightenment to a new Dark Age.

A ploy of Maxwell was to label his journals as global: instead of the parochial ‘British Journal of . . .’ it was always ‘International Journal of . . .’ In 1991 Maxwell sold his academic publishing empire to the Dutch publisher Elsevier for £440million. By then he had achieved his – and perhaps his secret sponsors’ – goal of a globally controlled academic press.

If a censorial conspiracy seems far-fetched, consider the case of the critical thinking journal Medical Hypotheses. Founded by British scholar David Horrobin in 1975, this journal published novel, radical ideas about health likely to be rejected by conventional journals. A single editor decided what to publish, with no review panel. In Patricia Kane’s obituary in the British Medical Journal, Horrobin was described as ‘one of the most original scientific minds of his generation’.

In 2009 Medical Hypotheses became a cause célèbre. Bruce Charlton, who succeeded Horrobin as editor-in-chief, accepted a highly controversial article by a Berkeley virologist. Peter Duesberg contested the HIV basis of Aids and argued that the South African government was right not to administer antiretroviral drugs to Aids sufferers because the HIV-Aids link remained unproven. Publication caused furore in the scientific world. Scientists associated with the US National Institutes of Health threatened to remove all subscriptions to Elsevier titles from the National Library of Medicine. Their demand was not only that Elsevier withdraw this article, but also to institute peer review at the journal.

Elsevier agreed and dismissed Charlton. Mehar Manku, who replaced him, assured that the journal would now ‘be careful not get into controversial subjects’, the reverse of what Horrobin intended. Charlton later remarked: ‘The journal which currently styles to itself Medical Hypotheses is a dishonest fake and a travesty of the vision bequeathed by the founder Professor David Horrobin; and as such it ought to be closed down – and on present trends it surely will be.’

The most significant use of academic journals for propaganda is with the ecological agenda. The supposedly overwhelming consensus for anthropogenic climate change is a myth, as the oft-cited figure of ‘97 per cent of scientists in agreement’ was derived from four studies, all of which were flawed. Science is not an opinion poll, and an appropriate rewording of the statement would be that 97 per cent of scientists believe in whatever gets them funding. Peer review has been exploited by the pharmaceutical industry. Antidepressant drugs have been consistently endorsed in medical journals since Prozac was introduced in the 1980s, despite dubious safety and effectiveness. This favouring of Big Pharma products reached its zenith with covid vaccines.

For the sake of humanity, we need to revert to an open and objective scientific enterprise. Like many purportedly progressive developments in society, peer review has brought more problems than it solves. That it was initiated by the rogue figure of Robert Maxwell, with secretive funding, suggests ulterior design.

This article appeared on Niall McCrae’s substack on October 16, 2025, and is republished by kind permission.

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/how-robert-maxwell-launched-global-control-of-academia